Should we invent “Vide Founding”?

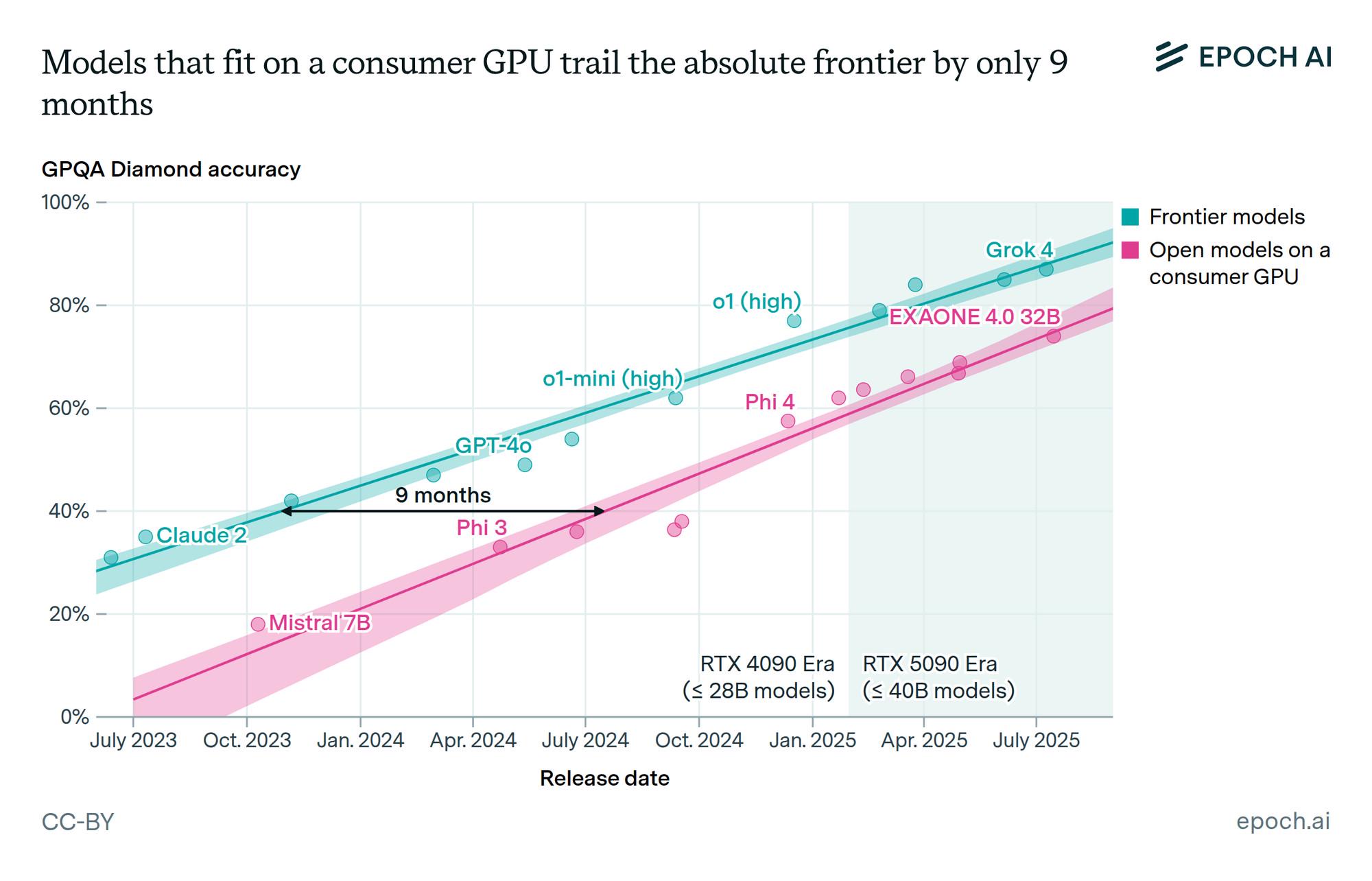

I find it astonishing to see so many new AI companies like Moonshot AI (Kimi 2) and Zhipu AI (GLM) building models and actually compete with Not-so-OpenAI. Even Grok is in the game, somehow.

While Apple can’t ship a working AI assistant 🫣.

In theory (and practice), Apple has unlimited money, the best talent, a billion devices, and the ecosystem that comes with that. The startups on the other hand just have smart people and funding. But then, Apple has those too, only more of them.

It’s the size. It matters. Apple’s size has stopped being an advantage, obviously. A startup can organize everything around AI while Apple has to add AI to a company that’s organized around hardware, retail, services, and a dozen other things. It’s like they’re renovating while people are living in the house.

It’s way easier to start something new than to change something that already exists, provided you have access to capital and talent. Musk figured this out (apparently). He’s basically invented Vibe Founding: you have enough money and personal brand that talented (if naive) engineers will join you, and you can spawn a new company, train absurdly large models, and compete with established players in a couple years. The fact that xAI burns through resources and ignores environmental regulations doesn’t seem to matter.

Oh, and Vibe founding has the same problem as vibe coding, though. Vibe coding gives you a prototype fast but leaves technical debt everywhere. Vibe founding gives you a company fast but the debt is ecological and social. Musk’s platforms amplify (his) misinformation and dangerous ideology at scale now. What we saw in the recent incidents is probably just the start.